- Understanding Breath-Holding Spells in Children: A Comprehensive Guide

- What Are Breath-Holding Spells?

- The Mechanism Behind the Spell

- Types

- Causes

- Symptoms

- Diagnosis

- Treatment and Management

- Medical Interventions

- Prevention

- Breath-Holding Spells in Children: Age-Specific Considerations

- When to See a Doctor

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding Breath-Holding Spells in Children: A Comprehensive Guide

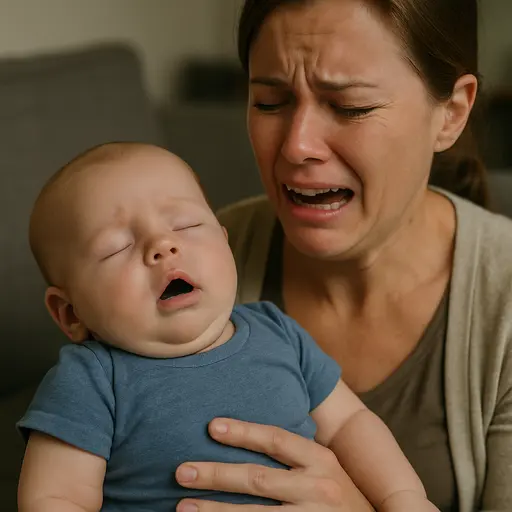

Breath-holding spells are a frightening yet surprisingly common phenomenon in early childhood. For a parent, witnessing a child suddenly stop breathing, turn blue or pale, and lose consciousness can be terrifying. However, despite their dramatic presentation, these episodes are generally benign and self-limiting events. This comprehensive guide aims to demystify the condition, exploring the breath-holding spells causes, clinical Symptoms, and management strategies to help parents navigate these episodes with confidence.

According to pediatric literature, the condition affects approximately 0.1% to 4.6% of otherwise healthy young children. These episodes are involuntary reflexes, not intentional behaviors, and they often occur in response to pain, frustration, or fear. While they can be distressing, understanding the mechanics behind a spell is the first step toward effective management and peace of mind. The term refers to a specific reflex, distinct from voluntary behavior.

What Are Breath-Holding Spells?

A spell is defined as a paroxysmal, non-epileptic event that occurs in children. It is characterized by an episodic cessation of breathing during expiration, which can lead to a loss of consciousness and changes in postural tone. Unlike voluntary breath-holding, where a child might hold their breath to be playful, true breath-holding spells are involuntary. The child does not have control over the onset of the spell, much like a reflex.

These events are frequently observed in young age groups. The onset is typically between 6 and 18 months of age, though occurrences in newborns have been rarely reported. The frequency of these events can vary significantly; some children may experience them sporadically, while others might have multiple episodes per day. Parents often search for information on these symptoms when they first witness these alarming episodes.

The Mechanism Behind the Spell

The physiology of breath-holding spells involves complex interactions between the respiratory system and the autonomic nervous system. When a child experiences a trigger—such as a sudden injury or an emotional outburst—the body reacts. In a cyanotic spell, the child cries forcefully, exhaling fully, and then fails to inhale. This leads to a rapid drop in blood oxygen levels and a decrease in cerebral blood flow, causing the child to faint. In pallid episodes, a vagal nerve response causes the heart rate to slow down (bradycardia), leading to a similar loss of consciousness.

Types of Breath-Holding Spells

There are two primary classifications of this condition: Cyanotic and Pallid forms. Understanding the distinction is crucial for proper diagnosis as the management and triggers can differ slightly between the two clinical presentations.

Cyanotic Breath-Holding Spells

Cyanotic types are the most common form, accounting for approximately 85% of cases. These are often associated with anger, frustration, or a temper tantrum.

- Trigger: The episode is usually precipitated by an emotional upset, such as being scolded or denied a toy.

- Sequence: The child starts to cry vigorously. Suddenly, the cry becomes silent as the child holds their breath in expiration. This is a classic presentation of a spell.

- Color Change: The child’s face, particularly around the lips, turns blue or purple (cyanosis) due to lack of oxygen.

- Outcome: The child may become limp or rigid and lose consciousness. In some cases, a brief seizure-like twitching may occur. Recovery is usually rapid, although the child may be tired afterward.

Pallid Breath-Holding Spells

Pallid types are less common and are distinct in their presentation and trigger.

- Trigger: These are typically triggered by a sudden fright, startle, or painful experience, such as a bump on the head.

- Sequence: Unlike the cyanotic type, there is often minimal or no crying. The child may give a single gasp or cry and then fall silent.

- Color Change: The child turns extremely pale or white (pallid) rather than blue.

- Outcome: The child loses consciousness quickly. This type is essentially a fainting spell (syncope) caused by a reflex (vasovagal response) that temporarily slows the heart.

Breath-Holding Spells Causes and Risk Factors

While the exact etiology remains multifactorial, researchers have identified several potential breath-holding spells causes. It is believed that a combination of physiological and environmental factors contributes to the occurrence of these spells.

Autonomic Nervous System Dysregulation

A prevailing theory suggests that children with breath-holding spells have an autonomic nervous system that is hypersensitive or dysregulated. This system controls involuntary bodily functions like heart rate and breathing. In these children, strong emotions or pain trigger an exaggerated response, leading to the breath-holding and subsequent fainting. Delayed myelination of the brainstem has also been proposed as a contributing factor, which explains why children typically outgrow the condition as their nervous system matures.

Iron Deficiency Anemia

There is a significant body of evidence linking breath-holding spells with iron deficiency anemia. Iron plays a crucial role in catecholamine metabolism and neurotransmitter function in the central nervous system. Studies have shown that a substantial percentage of affected children have low serum ferritin levels or frank anemia. Treating the iron deficiency often leads to a reduction in the frequency and severity of the spells, making iron status a critical component of diagnosis.

Genetic Factors

Genetics may also play a role. A positive family history is found in about 20% to 35% of cases. If a parent experienced similar episodes as a child, their offspring may be more predisposed to the condition. Specific genetic syndromes, such as Riley-Day syndrome or 16p11.2 microdeletion, are associated with severe forms of the disorder, leading to recurrent episodes.

Symptoms of Breath-Holding Spells

Identifying the symptoms accurately helps distinguish them from other conditions like epilepsy. The classic presentation includes:

- Provocation: A clear trigger (injury, anger, fear) immediately precedes the event.

- Crying: Usually present in cyanotic spells; often absent or brief in pallid spells.

- Apnea: A period of silence where breathing stops, typical of breath-holding spells.

- Color Change: Cyanosis (blue) or pallor (pale).

- Loss of Consciousness: The child becomes unresponsive.

- Posturing: The body may become stiff (tonic) or limp (hypotonic).

- Recovery: The child regains consciousness spontaneously, usually within a minute, without a postictal phase (confusion or drowsiness) typical of seizures.

Breath-Holding Spells Diagnosis

Breath-holding spells diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on a detailed history provided by the parents. A physician will look for the characteristic sequence of events: provocation, cry, silence, color change, and loss of consciousness.

To ensure accuracy, doctors may perform the following:

- Physical Examination: To rule out physical abnormalities.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): To rule out cardiac arrhythmias, such as Long QT syndrome, which can mimic the condition.

- Blood Tests: To check for iron deficiency anemia (Complete Blood Count, Ferritin).

- EEG (Electroencephalogram): Rarely needed, but may be used if the differentiation from epileptic seizures is difficult. Unlike epilepsy, the EEG in a child with this issue is normal between attacks.

It is important to differentiate the condition from other issues like reflux, seizures, or cardiac anomalies. If a spell occurs during sleep, feeding, or without a trigger, it requires immediate medical investigation as it is likely not a simple episode.

Breath-Holding Spells Treatment and Management

The cornerstone of breath-holding spells treatment is parental education and reassurance. Knowing that the child will not die during a spell and will recover spontaneously is vital.

Acute Management

When an episode occurs, parents should:

- Stay Calm: Panic can escalate the situation.

- Protect the Child: Lay the child on their side to prevent choking and protect the head from injury.

- Do Not Shake: Never shake the child to “snap them out of it,” as this can cause injury.

- Do Not Perform CPR: Unless the child does not resume breathing after the spell resolves (which is extremely rare), CPR is not necessary. The body’s natural reflexes will restart breathing.

- Observation: Time the spell. If it lasts longer than a minute, seek medical attention.

Medical Interventions

Medical management for children may involve specific therapies if the episodes are frequent or severe.

- Iron Supplementation: If iron deficiency is found (and sometimes even if iron levels are low-normal), iron supplementation (3-6 mg/kg/day) is highly effective. It has been shown to reduce the frequency of events significantly.

- Piracetam: Some studies suggest that Piracetam may be effective in reducing the frequency of episodes, possibly by improving cerebral oxygenation, though it is not a first-line treatment.

- Atropine: In severe cases of pallid spells associated with significant bradycardia (slow heart rate), atropine or glycopyrrolate may be prescribed to prevent the heart rate from dropping during episodes, though this is reserved for extreme cases.

Behavioral Management

For cyanotic spells triggered by tantrums, behavioral modification is key. Parents are advised not to reinforce the behavior. If a child learns that holding their breath results in getting their way, the frequency may increase. A consistent approach to discipline and avoiding triggers where possible can be helpful in managing the condition.

Breath-Holding Spells Prevention

Prevention of breath-holding spells focuses on managing the triggers and the child’s environment.

- Identify Triggers: Keep a diary to note what causes the spells (e.g., hunger, fatigue, specific frustrations).

- Distraction: If a child begins to cry or get angry, immediate distraction can sometimes abort the cycle before the breath-holding phase begins.

- Emotional Regulation: Helping toddlers develop emotional coping skills can reduce the intensity of tantrums.

- Rest and Nutrition: Ensuring the child is well-rested and fed can lower the irritability threshold.

- Iron Therapy: As a preventative measure, treating underlying anemia is the most proven method for prevention.

Breath-Holding Spells Age and Prognosis

The prognosis for children with breath-holding spells is excellent. It is a self-limiting condition.

- Onset: Typically between 6 and 18 months.

- Peak: The frequency often peaks around 2 years of age.

- Resolution: The vast majority of children outgrow the condition by age 5 or 6. By this age, the autonomic nervous system has matured, and the child has learned better emotional regulation.

- Long-term Effects: There is no evidence that the events cause brain damage or long-term cognitive impairment. The occurrence of these spells does not increase the risk of developing epilepsy later in life.

Breath-Holding Spells in Children: Age-Specific Considerations

Breath-Holding Spells in Infants (0-12 months)

For new parents, dealing with Breath-Holding Spells in infants can be a particularly terrifying experience. At this age, the cause is often physiological or related to pain (e.g., vaccinations). It is crucial to rule out other causes of apnea in this age group.

Breath-Holding Spells in Toddlers (1-3 years)

This is the peak age for cyanotic spells. The episodes are often intertwined with the “terrible twos” and temper tantrums. Management heavily relies on behavioral strategies and ensuring the child is safe during a drop attack. Youngsters of this age group often respond well to behavioral distraction.

Breath-Holding Spells in Babies vs. Older Children

While episodes in baby populations are often reactive to pain or sudden fear, older children often have spells triggered by complex emotional frustrations. In younger infants, these events require a thorough check to ensure no cardiac anomalies are present. During the toddler years, such occurrences are more likely to be cyanotic.

When to See a Doctor

While episodes are benign, consult a doctor if:

- This is the first episode.

- The child is under 6 months old (newborns or young infants need evaluation).

- The spells are accompanied by stiffening or shaking for more than a minute.

- The child takes a long time to recover or remains confused.

- The spells occur during sleep or feeding.

In conclusion, breath-holding spells are a common, benign, yet distressing part of childhood for many families. By understanding the causes, recognizing the Symptoms, and implementing appropriate strategies like iron supplementation and behavioral management, parents can navigate this challenging phase. Remember, the condition is involuntary, and with time and patience, your child will outgrow them.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can breath-holding spells cause brain damage?

No, breath-holding spells do not cause brain damage. Although the child loses consciousness due to a temporary lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain, the body’s failsafe mechanisms kick in immediately. Once the child faints, they relax, breathing resumes, and normal oxygen levels are restored long before any damage can occur to the brain tissue. Long-term studies have shown that children who experience these spells have normal neurological development and intelligence.

How to prevent breath-holding spells in infants?

Preventing Breath-Holding Spells in infants primarily involves managing the triggers and the environment. Since fatigue and hunger can lower an infant’s threshold for frustration, ensuring regular naps and feeding schedules is essential. Additionally, treating any underlying iron deficiency anemia with supplements prescribed by a doctor can significantly reduce or even eliminate the occurrence of the spells. Distraction techniques, such as showing a toy or making a funny noise right when the infant starts to cry, can also interrupt the cycle before the breath-holding begins.

What is breath holding spells?

A breath holding spell is an involuntary reflex that occurs in some children, usually between the ages of 6 months and 6 years. It is characterized by the child stopping breathing and losing consciousness for a short period, typically following a painful event, a fright, or an emotional upset like a tantrum. These spells are benign and self-limiting, meaning they are not harmful and children eventually outgrow them without lasting effects. They are classified into two main types: cyanotic (turning blue) and pallid (turning pale).

How to prevent breath-holding spells in infants?

To prevent Breath-Holding Spells in infants, parents should focus on minimizing stress and frustration for the child. This includes avoiding situations that are known to trigger excessive crying or tantrums whenever possible, though this is not always feasible. Medical prevention is also critical; having the infant screened for iron deficiency and treated if necessary has been proven to be very effective. Furthermore, parents can learn to recognize the early signs of a spell and use immediate distraction or soothing techniques to calm the infant before the spell progresses to the point of breath-holding.

The following posts may interest you

Is it normal for a newborn to breathe fast? Expert Guide

Is swaddling safe and when to stop: A Parent’s Guide

Baby Wheezing: Causes, Treatments, and When to Worry

Bronchiolitis: Symptoms, Causes, and Management Guide

Pneumonia in Babies: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Sources

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0887899496000069

https://adc.bmj.com/content/81/3/261.abstract

https://scholar.google.com/scholar?start=10&q=breath-holding+spells&hl=tr&as_sdt=0,5

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jpc.13556

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02080.x

https://www.benthamdirect.com/content/journals/cpr/10.2174/1573396314666181113094047

https://www.cfp.ca/content/61/2/149.short

https://adc.bmj.com/content/66/2/255.abstract

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/516018